MRPolo13

The Arbiter of the Gods

So this thread was revived: http://hollowworld.co.uk/threads/armour-to-consider.20394/ and at the outset it is severely outdated. So instead of revamping it I might as well create a new thread, talking about armour and spreading my knowledge like a cheap hooker's legs.

There are a few misconceptions in that thread. Firstly is the variety of clothing that I have included. For some bizzare reason 2013 me listed a tunic as a form of armour clothing without mentioning the many other types of clothes present in the Medieval period. Specifically, mid-15th century fashion since the tech is cut off at that point. Obviously tunics were around, but stiff doublets were more popular amongst nobility. It's a long subject so for this reason clothing isn't included, though it might be interesting to note that clothing and armours developed sort of alongside each other, with one taking inspiration from the other.

Anyway, the second misconception is that I used leather armour as an example. Let's just ignore I ever said that. Leather armour did exist - the buff coat was popular in 16th century England, specifically popular during the English Civil War, but it appears to have been used mostly as an undergarment for the cuirasses that soldiers would wear. The civil war is, after all, the time of England realising the advantages of a professional standing army that was funded by the state. Sooner or later everyone would come around to that idea. But leather wasn't a good armour because while it can survive a cut it's harder to repair, expensive, you need a lot of it to cover the body, and if you can afford that you can probably also afford a gambeson. I actually think that buff coats look great, but just don't see their utility versus gambeson. You can also boil leather differently to be like plastic. That's how Romans would shape their 'Lorica Musculata' as some like to call it.

A buff coat at Royal Armouries. They'd usually be lighter in colour - more yellowish than brown.

Studded leather is even worse. In actuality "studded" leather is most likely a coat of plates or, by our time period, a brigandine. We'll get onto that in a moment.

So, what armour to actually consider? First we have the gambeson/arming jacket. A gambeson is a padded coat, usually made out of wool or linen. The padding used could be scraps of cloth, horse hair or anything that can... well... pad out the armour. This meant that the material required was inexpensive and ultimately the gambeson was cheap. There IS a difference between a normal gambeson and an arming jacket. For the sake of this argument just say that a gambeson is expected to be worn alone and has therefore got a lot more padding while an arming jacket can have almost no padding at all. Furthermore, some arming doublets could have mail attached to them in places that are otherwise not protected by plate armour. As for the fashion of these it's difficult to say. It appears that at least some doublets were tailored to resemble actual civil use doublets, so they had puffy shoulders. That's not a universal truth, of course. Just bear in mind that if your gambeson is worn under armour it's probably thin and won't protect you well on its own. If it's a standalone gambeson (whether not as part of a set or simply to be worn alone or with mail over it) then it's probably fairly thick and offers good protection against most types of attack. Also be careful when looking at modern depictions. As with everything they tend to be overbuilt for safety. This is not always historically accurate.

A recreation of an Italian arming doublet from 1435-1445. As you can see, while thicker than normal clothing it's not really that thick.

We can then talk about mail armour. This armour hasn't really changed that much since antiquity. There are many intricate pattern changes that I don't understand very well, which give people that specialise in this subject an idea of when the mail comes from. Basically, although mail was generally 'riveted' there were often links that were not. Some rings were welded/stamped. Also, mail rings had very little gaps, and you should never say that your mail is certain size in diameter. Remember that all of this was handmade so different parts of the body got different ring thicknesses/diameters. You'd want very fine rings around your neck, for instance, and the bascinet from Wallace Collection is what I often bring up to show just how small these rings were. Generally it's best to just say that you're wearing tailored mail. Furthermore by mid-15th century hauberks (full shirts of mail) fell out of popular use with the knightly class. If you're wearing a full, custom-made plate armour you're most likely wearing either an arming jacket with mail or separate mail sleeves and other bits to go over the areas that armour does not cover. Mail armour is very heavy, you want to avoid using it where you don't have to. Once again this comes down to your budget though. Most soldiers would probably buy their armour in pieces, so they'd probably have a full shirt of mail first and then buy the armour on top of it.

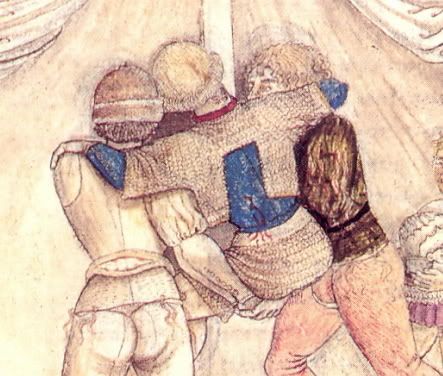

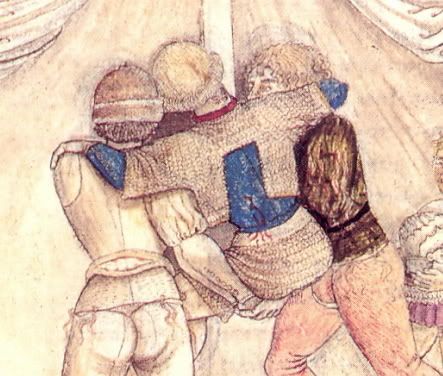

Mid-15th century painting of a wounded knight. as you can see, he is wearing a mail skirt and voiders, as opposed to a full mail shirt. This saves a lot of weight over the torso where the cuirass is protecting you anyway. Painted by Pisanello.

Next we have plate armour. This is where I diverge into two categories of plate armour: Milanese and Gothic. But before I do let's get the obvious stuff out of the way first. Plate armour GENERALLY is not heavy. It allows great mobility while being highly protective. It does not make you invincible, you're actually fairly vulnerable from more than one person (if they're even slightly armoured), your vision is so screwed and have fun breathing inside of a tin can. When you wear armour, which you shouldn't do constantly unless you're an idiot, you find that heat gets hotter and if it's cold you might start sweating. Anyone who knows anything about sweating in cold will tell you that it's a bad idea. Also most knights who died in armour died with their visors up, so that gives you an idea as to just how difficult breathing could be after a long, exhausting battle.

So, Gothic armour.

This bad boy is a set of Gothic armour, which originated in Germany in roughly 15th century and spread in popularity from there. Especially common nowadays are cheap, Indian-made knockoffs of the gauntlets. Gothic armour was characterised by fluting. Flutes are small (often smaller than modern reproductions show) ridges struck into the metal, which theoretically provide additional rigidity to the structure. In 16th century we'd see the Germans take their love for fluting to the extreme with Maximilian style of plate armour, but right now fluting was relatively limited. This armour was generally symmetrical - another characteristic of it - and had a sallet, which is the helmet you see above. A sallet was a 'short' helmet that usually went down to just below your nose. The rest of the way was protected by the bevor, which was a separate piece that you can see on the image above.

My personal favourite: Milanese armour. These armours were made in 15th century Italy, hence their name. Although called Milanese they were produced all across Italy. This example is pretty much perfect for showing the concept of the armour. Left hand side, the one expected to receive the most blows, is protected more than right side. This armour also introduces substantial pauldrons, which were not really a feature of earlier plate armours of the 14th century. The right pauldron is cut away to expose the armpit slightly, so that the knight could rest his lance easily without the pauldron getting in the way. The four holes in the chestplate would have a lance rest attached to them, which was a metal hook that would allow you to, you guessed it, rest your lance. You'd often see either an armet (though at this stage the armet would have a fairly short nose to it, just keep that in mind) or a barbute as helmets on this armour. Northern Italian armours take it a step further by getting some of that sweet influence from Germans and pimping out their armours with a few cheeky flutes. Always a plus in my book.

Early in 15th century there was also a distinct English style of plate armour, but by mid-15th century they mostly imported or were inspired by either the Milanese or Gothic schools of thought. Now, you must understand that this isn't at all a universal truth. There were gothic armours with armets, Italian armours with sallets, as many variations as there were armours in existence.

So what about the common soldier? Well, they'd probably buy their armour pieces separately. First and foremost by this point the vast majority of soldiers had some sort of plate armour, even longbowmen and foot soldiers. You'd probably buy your armour one piece at a time, starting with gambeson and mail and a helmet of some sort. Then your next purchase might be a cuirass - that's where brigandines come in handy.

A brigandine is a series of small metal plates riveted to a material or leather. I should hasten to add that leather is probably not the best material to use for this, for reasons I pointed out above. In this time period, material was often more expensive than labour, especially at the lower level of armourers that the common soldier would be buying from. Brigandines are great because they're smaller plates riveted to the leather, instead of a single large plate, so scraps can be used to full effect. As for helmets, munition-grade sallets were basically mass produced by mid-15th century, with growing power of cities over landowners which meant that armies became larger and had to be supplied cheaper. It's a long story.

So just how thick was this plate armour? As you know, plate armour is fairly light - at the highest end jousting armour could weigh 50 kilos, but it usually weighed up to 25 kilo. Taking this measurement and averaging it out shows that the average thickness of the heaviest combat armours was around 1.6mm (according to this: http://www.thyssenkruppaerospace.com/materials/steel/steel-sheet-plate/weight-calculations.html). This isn't, of course, an absolute - an armour would vary in thickness everywhere because it was hand made and because some parts don't need to be as protected as others. So, the beak of your cuirass will be thick, while your vambraces and greaves are probably going to be less than a millimetre. Helmets were often the thickest parts, for fairly obvious reasons. Furthermore, this is at its heaviest. Modern reproductions vary between 14 gauge (~2mm) and 18 gauge (~1.2mm). This is very thick for even iron armour of the Medieval period, and is an obvious concession for safety at the expense of mobility. I'd say that the 2mm figure is probably the most you'll see in a historical plate armour, aside from the helmet that went up all the way to 4mm. The thing is that there isn't really a point in making armour thicker though, because it will still protect you from almost anything without costing you a ton of money just to have difficulties standing upright. Double thickness means double weight, and even an extra kilogram can be painful at times. Then again, trying to measure the thickness of your armour is idiotic anyway, and pedantically aims to quantify something as we modern people like to do, while in reality quantifying was never that important historically. I reiterate that armour differed in thicknesses, which further helped with balancing on your hot bod, so it's not even that easy to quantify if you wanted to.

There are a few misconceptions in that thread. Firstly is the variety of clothing that I have included. For some bizzare reason 2013 me listed a tunic as a form of armour clothing without mentioning the many other types of clothes present in the Medieval period. Specifically, mid-15th century fashion since the tech is cut off at that point. Obviously tunics were around, but stiff doublets were more popular amongst nobility. It's a long subject so for this reason clothing isn't included, though it might be interesting to note that clothing and armours developed sort of alongside each other, with one taking inspiration from the other.

Anyway, the second misconception is that I used leather armour as an example. Let's just ignore I ever said that. Leather armour did exist - the buff coat was popular in 16th century England, specifically popular during the English Civil War, but it appears to have been used mostly as an undergarment for the cuirasses that soldiers would wear. The civil war is, after all, the time of England realising the advantages of a professional standing army that was funded by the state. Sooner or later everyone would come around to that idea. But leather wasn't a good armour because while it can survive a cut it's harder to repair, expensive, you need a lot of it to cover the body, and if you can afford that you can probably also afford a gambeson. I actually think that buff coats look great, but just don't see their utility versus gambeson. You can also boil leather differently to be like plastic. That's how Romans would shape their 'Lorica Musculata' as some like to call it.

A buff coat at Royal Armouries. They'd usually be lighter in colour - more yellowish than brown.

Studded leather is even worse. In actuality "studded" leather is most likely a coat of plates or, by our time period, a brigandine. We'll get onto that in a moment.

So, what armour to actually consider? First we have the gambeson/arming jacket. A gambeson is a padded coat, usually made out of wool or linen. The padding used could be scraps of cloth, horse hair or anything that can... well... pad out the armour. This meant that the material required was inexpensive and ultimately the gambeson was cheap. There IS a difference between a normal gambeson and an arming jacket. For the sake of this argument just say that a gambeson is expected to be worn alone and has therefore got a lot more padding while an arming jacket can have almost no padding at all. Furthermore, some arming doublets could have mail attached to them in places that are otherwise not protected by plate armour. As for the fashion of these it's difficult to say. It appears that at least some doublets were tailored to resemble actual civil use doublets, so they had puffy shoulders. That's not a universal truth, of course. Just bear in mind that if your gambeson is worn under armour it's probably thin and won't protect you well on its own. If it's a standalone gambeson (whether not as part of a set or simply to be worn alone or with mail over it) then it's probably fairly thick and offers good protection against most types of attack. Also be careful when looking at modern depictions. As with everything they tend to be overbuilt for safety. This is not always historically accurate.

A recreation of an Italian arming doublet from 1435-1445. As you can see, while thicker than normal clothing it's not really that thick.

We can then talk about mail armour. This armour hasn't really changed that much since antiquity. There are many intricate pattern changes that I don't understand very well, which give people that specialise in this subject an idea of when the mail comes from. Basically, although mail was generally 'riveted' there were often links that were not. Some rings were welded/stamped. Also, mail rings had very little gaps, and you should never say that your mail is certain size in diameter. Remember that all of this was handmade so different parts of the body got different ring thicknesses/diameters. You'd want very fine rings around your neck, for instance, and the bascinet from Wallace Collection is what I often bring up to show just how small these rings were. Generally it's best to just say that you're wearing tailored mail. Furthermore by mid-15th century hauberks (full shirts of mail) fell out of popular use with the knightly class. If you're wearing a full, custom-made plate armour you're most likely wearing either an arming jacket with mail or separate mail sleeves and other bits to go over the areas that armour does not cover. Mail armour is very heavy, you want to avoid using it where you don't have to. Once again this comes down to your budget though. Most soldiers would probably buy their armour in pieces, so they'd probably have a full shirt of mail first and then buy the armour on top of it.

Mid-15th century painting of a wounded knight. as you can see, he is wearing a mail skirt and voiders, as opposed to a full mail shirt. This saves a lot of weight over the torso where the cuirass is protecting you anyway. Painted by Pisanello.

Next we have plate armour. This is where I diverge into two categories of plate armour: Milanese and Gothic. But before I do let's get the obvious stuff out of the way first. Plate armour GENERALLY is not heavy. It allows great mobility while being highly protective. It does not make you invincible, you're actually fairly vulnerable from more than one person (if they're even slightly armoured), your vision is so screwed and have fun breathing inside of a tin can. When you wear armour, which you shouldn't do constantly unless you're an idiot, you find that heat gets hotter and if it's cold you might start sweating. Anyone who knows anything about sweating in cold will tell you that it's a bad idea. Also most knights who died in armour died with their visors up, so that gives you an idea as to just how difficult breathing could be after a long, exhausting battle.

So, Gothic armour.

This bad boy is a set of Gothic armour, which originated in Germany in roughly 15th century and spread in popularity from there. Especially common nowadays are cheap, Indian-made knockoffs of the gauntlets. Gothic armour was characterised by fluting. Flutes are small (often smaller than modern reproductions show) ridges struck into the metal, which theoretically provide additional rigidity to the structure. In 16th century we'd see the Germans take their love for fluting to the extreme with Maximilian style of plate armour, but right now fluting was relatively limited. This armour was generally symmetrical - another characteristic of it - and had a sallet, which is the helmet you see above. A sallet was a 'short' helmet that usually went down to just below your nose. The rest of the way was protected by the bevor, which was a separate piece that you can see on the image above.

My personal favourite: Milanese armour. These armours were made in 15th century Italy, hence their name. Although called Milanese they were produced all across Italy. This example is pretty much perfect for showing the concept of the armour. Left hand side, the one expected to receive the most blows, is protected more than right side. This armour also introduces substantial pauldrons, which were not really a feature of earlier plate armours of the 14th century. The right pauldron is cut away to expose the armpit slightly, so that the knight could rest his lance easily without the pauldron getting in the way. The four holes in the chestplate would have a lance rest attached to them, which was a metal hook that would allow you to, you guessed it, rest your lance. You'd often see either an armet (though at this stage the armet would have a fairly short nose to it, just keep that in mind) or a barbute as helmets on this armour. Northern Italian armours take it a step further by getting some of that sweet influence from Germans and pimping out their armours with a few cheeky flutes. Always a plus in my book.

Early in 15th century there was also a distinct English style of plate armour, but by mid-15th century they mostly imported or were inspired by either the Milanese or Gothic schools of thought. Now, you must understand that this isn't at all a universal truth. There were gothic armours with armets, Italian armours with sallets, as many variations as there were armours in existence.

So what about the common soldier? Well, they'd probably buy their armour pieces separately. First and foremost by this point the vast majority of soldiers had some sort of plate armour, even longbowmen and foot soldiers. You'd probably buy your armour one piece at a time, starting with gambeson and mail and a helmet of some sort. Then your next purchase might be a cuirass - that's where brigandines come in handy.

A brigandine is a series of small metal plates riveted to a material or leather. I should hasten to add that leather is probably not the best material to use for this, for reasons I pointed out above. In this time period, material was often more expensive than labour, especially at the lower level of armourers that the common soldier would be buying from. Brigandines are great because they're smaller plates riveted to the leather, instead of a single large plate, so scraps can be used to full effect. As for helmets, munition-grade sallets were basically mass produced by mid-15th century, with growing power of cities over landowners which meant that armies became larger and had to be supplied cheaper. It's a long story.

So just how thick was this plate armour? As you know, plate armour is fairly light - at the highest end jousting armour could weigh 50 kilos, but it usually weighed up to 25 kilo. Taking this measurement and averaging it out shows that the average thickness of the heaviest combat armours was around 1.6mm (according to this: http://www.thyssenkruppaerospace.com/materials/steel/steel-sheet-plate/weight-calculations.html). This isn't, of course, an absolute - an armour would vary in thickness everywhere because it was hand made and because some parts don't need to be as protected as others. So, the beak of your cuirass will be thick, while your vambraces and greaves are probably going to be less than a millimetre. Helmets were often the thickest parts, for fairly obvious reasons. Furthermore, this is at its heaviest. Modern reproductions vary between 14 gauge (~2mm) and 18 gauge (~1.2mm). This is very thick for even iron armour of the Medieval period, and is an obvious concession for safety at the expense of mobility. I'd say that the 2mm figure is probably the most you'll see in a historical plate armour, aside from the helmet that went up all the way to 4mm. The thing is that there isn't really a point in making armour thicker though, because it will still protect you from almost anything without costing you a ton of money just to have difficulties standing upright. Double thickness means double weight, and even an extra kilogram can be painful at times. Then again, trying to measure the thickness of your armour is idiotic anyway, and pedantically aims to quantify something as we modern people like to do, while in reality quantifying was never that important historically. I reiterate that armour differed in thicknesses, which further helped with balancing on your hot bod, so it's not even that easy to quantify if you wanted to.